The Bank of England, founded in 1694, operated for much of its early history as a private company, although its relationship with the state was complex and evolving. It played a major role in financing government borrowing, including helping to fund a number of wars. Without doubt, the Bank of England’s origins provide a fascinating story of trust, debt and economic innovation against a backdrop of war and royal extravagance. In the 17th century, ‘banking’ in England was mostly carried out by goldsmiths who offered loans and safeguarded valuables for the wealthy. These goldsmith-bankers charged exorbitant interest rates, sometimes 20-30%, and became the main lenders to the monarchy. But in 1672, King Charles II, having lived beyond his means, defaulted on debts owed to the goldsmiths, shattering confidence in private lenders and destabilising England’s short-term credit system.

The Bank of England being formed in 1694

Source: X

This royal default had far-reaching consequences and, with goldsmiths unwilling to lend further to monarchs, by the 1690s, the English Crown was left with a deepening financial crisis. To cap it all, a new war with France, (William III’s Nine Years’ War), exacerbated the need for funds to support the rebuilding of the navy and military. But traditional borrowing sources such as goldsmiths simply refused. Therefore, the Crown required a way out, a means to raise significant capital efficiently, reliably and at a reasonable interest rate. So, in 1694, what we now know as the Bank of England was created. Members of the public were invited to subscribe a total of £1.2 million (equivalent to around £200 million today). In just eleven days, 1,268 people invested in the shares of ‘the Governor and Company of the Bank of England’. Significantly, it proved far more successful, nimble and secure than previous systems - investors trusted that their funds were protected from royal interference and subject to the rule of law, not royal whim. The Bank was formally founded by Royal Charter on July 27, 1694, with William III and Queen Mary amongst its original stockholders.

Initially, the institution operated as both a bank for the government and a private corporation serving shareholders, with its mandate “to promote the public good and benefit of our people”, a statement that remains in the mission today. This can be seen recorded in the Bank of England Museum where it is explained that: “People invested in it by purchasing ‘bank stock’ and the government paid them 8% interest. It was a good deal for the government as goldsmiths charged lending rates of more than twice that amount!” The Bank of England remained a private company for 250 years and even George Washington had a personal shareholding in the institution. In addition, the Bank of England helped the British government fund the battles against Washington whilst George Washington was paid a dividend on his shareholding. Such irony! The legacy of goldsmith failures and royal defaults created a unique moment in British history; the Bank’s joint-stock structure channelled national financial power into an innovative model that foreshadowed central banking as we know it. The lessons are profound - trust, shared risk and transparency, born out of the disaster of monarchical default, became the backbone of capital infrastructure able to fund state needs far beyond what private sector lenders could offer. In 1946, the UK debt was 252% of GDP and the UK government decided to nationalise its very institution, the Bank of England, that had for over 200 years helped finance the nation’s borrowings.

So, what lessons does history potentially offer us now? The US has currently has over $37trillion of debt and some estimate predict that US borrowings could balloon to over $138 trillion by the end of 2055. Meantime, the US is encouraging global dollarisation and has introduced the GENIUS Act as a means to stimulate demand for US dollar stablecoins, underpinned by short term US treasuries. The different between 91 day US bills and 30 years treasury bonds is approximately 0.7%, which equates to a saving of $7billion p.a. in interest charges for every trillion of debt. Therefore, given the US debt is $37trillion, if the US were able to save 0.7% on its entire current borrowing, it would save each year $259billion in interest. So, unless the books start to balance, some predict the US government debt ratio will reach 133% of GDP by 2030 - beating forecasts for France (120%) and the UK (110%) - whilst interest payments will exceed 12% of revenues, which is at least twice that of its peers. In the meantime, drawing a parallel to the US debt trajectory, some speculate that its debt could similarly become “too big to manage” in the future, raising questions about the sustainability of current fiscal policies and furthermore questioning the ability of the US dollar to remain the world’s reserve currency.

Hence, with this in mind, could one course of action be for a US administration to nationalise MicroStrategy? Arguably, MicroStrategy’s history and focus on Bitcoin acquisitions mirrors the US’s historic campaign of territorial expansion. Just as the US grew from fragile colonies to a continental superpower by bold purchases, such as Louisiana from the French in 1803 for $15million and Alaska from the Russians in 1867 for $7.1 million, MicroStrategy, under Michael Saylor, pivoted in 2020 from corporate analytics to aggressive Bitcoin buying - even when critics doubted the outcome. By late 2024, MicroStrategy held 446,400 BTC, mirroring ambitious US land grabs such as Texas and California. This endurance through price swings recalls frontier challenges, capped by recent purchases paralleling Alaska’s controversial acquisition (which ultimately proved wise). Both journeys were steered by visionary leaders ready to withstand criticism and take bold financial gambles. MicroStrategy’s moves, issuing equity and debt so as to continually expand BTC reserves, demonstrates the kind of strategic, multi-stage growth that defined America’s continental rise.

Without doubt, MicroStrategy Bitcoin holdings could be seen as a modern financial bet of staggering scale, having taken on over $8.1billion of debt in order to acquire 640,031 of BTC. However, if Bitcoin’s price ever surges to $10m million per coin, as predicted by CEO, Michael Saylor, then MicroStrategy’s digital asset portfolio would be valued at over $6.4 Trillion. This positions MicroStrategy as a uniquely leveraged entity in the crypto-assets space, with immense exposure to Bitcoin price movements that could rival sovereign debt markets. Indeed, it is possible that MicroStrategy could accumulate twice the number of Bitcoin it currently owns, which means it could have over $12trillion of Bitcoin. Now that surely begins to look very appealing to a cash-strapped government. If you add to this the current 197,000 BTC that the US government owns (at $10million a Bitcoin) then, if the US government nationalised MicroStrategy, it would have almost $14trillion worth of Bitcoin - assuming it acquires/does not confiscate any other Bitcoins from other nefarious actors.

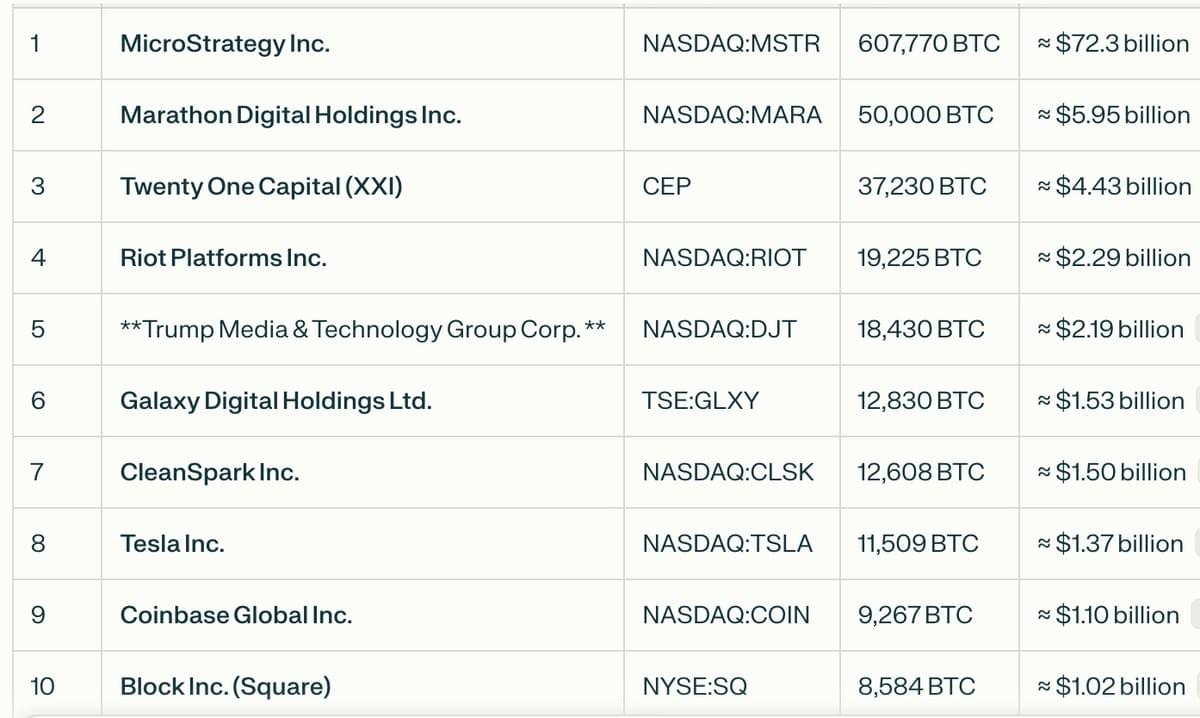

US companies that have Bitcoin treasuries

Source: CoinGeko

Hence, whilst the Bank of England represents a matured, government-controlled monetary authority, MicroStrategy symbolises a high-risk, high-reward private corporate strategy focused on digital assets. The key difference lies in the former’s role as a central bank with broad policy objectives, versus the latter’s commercial and speculative motivations. Moreover, could MicroStrategy’s Bitcoin holdings lead to a shift in financial sector dominance or even provoke

government intervention akin to the Bank of England’s nationalisation? Although speculative, such questions highlight how the rapid growth of digital assets and corporate treasuries are reshaping traditional financial paradigms. After all, could a US government take control of Bitcoin treasuries in the same way it nationalised gold in the great depression in 1930’s? Certainly, this evolving dynamic warrants monitoring because of potential implications for financial stability, regulatory policy and the intersection between sovereign finance and private digital asset accumulation. And with US government debt projected to grow significantly over the next two decades, the interplay between public debt institutions and major crypto holders such as MicroStrategy will remain critical to understanding future fiscal and monetary landscapes.

Yes, the Bank of England’s nationalisation in 1946 is a real historical event but, no, it does not provide a clean blueprint for the nationalisation of a company such as MicroStrategy. The functions, context and legal regimes differ fundamentally. However, that said, MicroStrategy’s massive Bitcoin holdings and debt profile mean it is no longer simply a software company - it is arguably a financial speculator and reserve asset holder. The intellectual exercise of “could the government step in?” may seem far-fetched today, but it underscores the evolving frontier where corporations are bridging technology, finance and “money” in ways that challenge regulatory frameworks and sovereignty assumptions. In that sense, what we should focus on is not whether MicroStrategy and indeed other Bitcoin corporate treasuries (the top nine corporate holders of Bitcoin after MicroStrategy own a further 179,000+ Bitcoins) will be nationalised, but how regulators and policymakers will adapt to entities that act more akin to digital-asset treasurers than traditional corporations.

This article first appeared in Digital Bytes (28th of October, 2025), a weekly newsletter by Jonny Fry of Team Blockchain.